I was recently helping a friend make a family history video. He had written an introductory piece that he wanted to deliver to camera outside an old country pub once owned by his forbears. This seemed very straightforward. I hooked up a lavelier (lapel) mike to the camera and positioned him with the pub in the background. It started well until the nearby ice machine cranked up. We then moved across the road and started again. This time the sound of a chainsaw from a neighbouring property rent the air. It was time to take a break. After peace was restored we battled on pausing for passing tractors and other farm machinery, and the odd car.

Like most of us, my “talent” was also having trouble remembering more than a about one paragraph at a time. “Not too worry,” I thought, “I’ll insert cutaways to old photos and other footage to cover these breaks”. However, it was a partially cloudy day and the light kept changing by the second. Even within the shorter takes, the change in lighting was very noticeable. Not only that, but every time the sun appeared my talent squinted his eyes. Thankfully we did not also have to contend with people moving around in the background, aircraft flying overhead, or that other great bane of videographers, wind. Nonetheless, back in the editing suite, I had the Devil’s own job of making something useable out of it all.

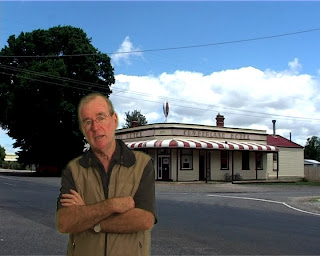

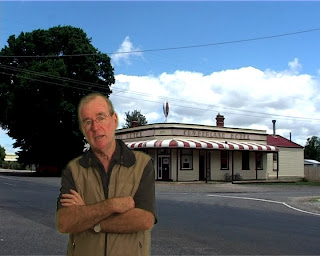

Fortunately, I had taken some long shots of the old pub without people in them. So we decided to try again using chroma-key. I erected my green screen sheet in my family room-come-studio and had my talent re-do his introduction. In only two or three takes we had it down pat and in the can. The lighting was better and so was the sound. Fortunately, no extraneous motor mowers were going in the neighbourhood. My talent was more relaxed and natural. With a bit of a fiddle in Premiere Pro, and the judicious use of cutaways, I am confident that we will get away with it.

So, if you are making a documentary or perhaps a video about your holiday travels, you might like to try using chroma key. However, there are some points to remember. These relate to both shooting the location footage, and to filming the presentation.

So, if you are making a documentary or perhaps a video about your holiday travels, you might like to try using chroma key. However, there are some points to remember. These relate to both shooting the location footage, and to filming the presentation.

Avoid using stills as background, especially if they have people, water, trees or vehicles in them. The audience will be looking for these to move. If you are shooting location footage with a view to using as a chroma key background, make sure your camera is rock solid by using a tripod or otherwise securing your camera. Do not pan, tilt or zoom. Use a long shot rather than a wide shot. Record the shot for at least as long as think your talent might be speaking in front of it. You might get away with extending the clip by slowing it down in editing, but not if there are people or moving vehicles in it. Shoot plenty of other footage around the location. These will be used as cutaways from the “to camera” presentation.

In setting up your “studio” to shoot the presentation, make sure you have plenty of room; at least 5 metres from camera to green screen. Your green screen should be as flat and as dull as possible. I have used the green screen provided with Pinnacle Studio 11, and it works extremely well. If the screen has sharp creases, iron them out before use. Creases can show up as colour variations and may be impossible to remove in editing. Secure the screen at at least three points across the top and three points across the bottom and ensure that it is quite taut. The top of the screen should be about two metres above the floor.

You should light the green screen separately from your talent. I used two work-lights placed on chairs to each side of the screen and about 1.8 metres out from the screen. The chairs had solid backs that prevented these lights spilling directly on to my talent. Spilt light like this could cause highlights on the talent’s shoulders and hair that can make it difficult for the editing program to separate cleanly from the background.

The talent should be placed about the two metres out from the screen so that he or she is seen from the camera against the green background from head to waist height. In lighting my talent, I used a modified* work-light, bounced from the ceiling. This light was placed to one side of the camera. While not pure studio lighting, it was more credible as outdoor lighting. In all cases you will need to ensure that no shadows from the talent are visible on the green screen.

The camera was placed about 3 metres in front of the talent and the shot was framed with a medium zoom so that the background was visible all around the talent. Placing the camera too close makes it harder to ensure that sufficient green screen is visible around the talent. A medium zoom is also favoured by portrait photographers; it provides a more natural and less distorted picture of the face.

The camera was placed about 3 metres in front of the talent and the shot was framed with a medium zoom so that the background was visible all around the talent. Placing the camera too close makes it harder to ensure that sufficient green screen is visible around the talent. A medium zoom is also favoured by portrait photographers; it provides a more natural and less distorted picture of the face.

Do not be overly worried if the green screen does not fully fill the frame. The extraneous backgrounds can be removed in editing.

Having recorded the presentation, it is time to hit the editing suite. The following is based on using Premiere Pro, but the principles should apply to any good editing product.

Place the presentation footage on track 2.

Edit the footage so that the presentation flows smoothly.

Place the location footage on track 1.

Lower the volume on the location audio track.

In the first presentation clip on track 2, resize and re-position the talent against the location. You can temporarily reduce the opacity so as to see the background through the clip (don’t forget to return to full opacity once this is done).

Apply the green-screen key to the first clip on track 2.

Adjust the controls until the green background disappears.

Use a garbage matte to remove any other extraneous background images.

The talent should now appear in front of the location footage.

Adjust the lighting and colour of the talent to blend with the location footage.

Copy the first clip on track 2

Highlight the remaining clips on track 2 and “paste attributes”.

Place your cutaway clips on track 3, trimming and positioning as you go. These clips should be placed to cover any cuts between clips on track 2, and/or to illustrate any particular references made in the presentation.

If you can master these techniques, you will find that you can add extra dimensions to your videos, and you can make presentations to camera with more control, in less time, and without having to make a goose of yourself in public.

*I used an angle grinder to “soften” the glass lens of the work-lights.